A New Century

As homesteaders in the valley became farmers, and as the community of Glen Ellen began to grow, commitment to a vision of future possibilities, including social responsibilities began to appear. A state home for severely disabled children was established nearby, bringing people engaged in social services. A major literary figure adopted our valley as his chosen home, and a significant patron of the arts established her ranch, where much of the planning of WWII took place.

The State Home at Eldridge

In 1883 Julia Judah and Frances Bentley, two prominent California women who had children with developmental disabilities, established the California Association for the Care and Training of Feeble Minded Children. Its aim was “to provide and maintain a school and asylum for the feeble-minded, in which they may be trained to usefulness.” After casting about for locations for their institution, Captain Oliver Eldridge helped them purchase 1,640 acres near Glen Ellen from William McPherson Hill, and on November 24th, 1891, the facility opened its doors to 148 residents.

The facility at Eldridge has undergone many significant changes over the years since then, including four name changes— each reflecting significant changes in the attitudes, philosophies, values, and beliefs in the treatment of severely disabled people. In 1909 the name was changed from the California Home for the Care and Training of Feeble Minded Children to the Sonoma State Home, in 1953 it became the Sonoma State Hospital, and in 1986 it became the Sonoma Developmental Center, or SDC.

The importance of this institution to the Valley of the Moon, and to Glen Ellen cannot be overlooked. The institution has always been our greatest local employer, and its presence has always brought caring, altruistic people to live here in order to work with some of the most severely disabled people in all of California.

It can easily be said that the facility at Eldridge helped shape the character of our village as a gentle, friendly, and sometimes edgy place throughout the Twentieth Century, and that Eldridge and Glen Ellen grew up together over the years. Most people who have lived in Glen Ellen have worked in Eldridge, or are friends of people that have worked there— from the ones that provide direct care for the residents to those that provide all the necessary administrative and ancillary support, such as the police, fire and food services.

Dr. Charles C. O’Donnell

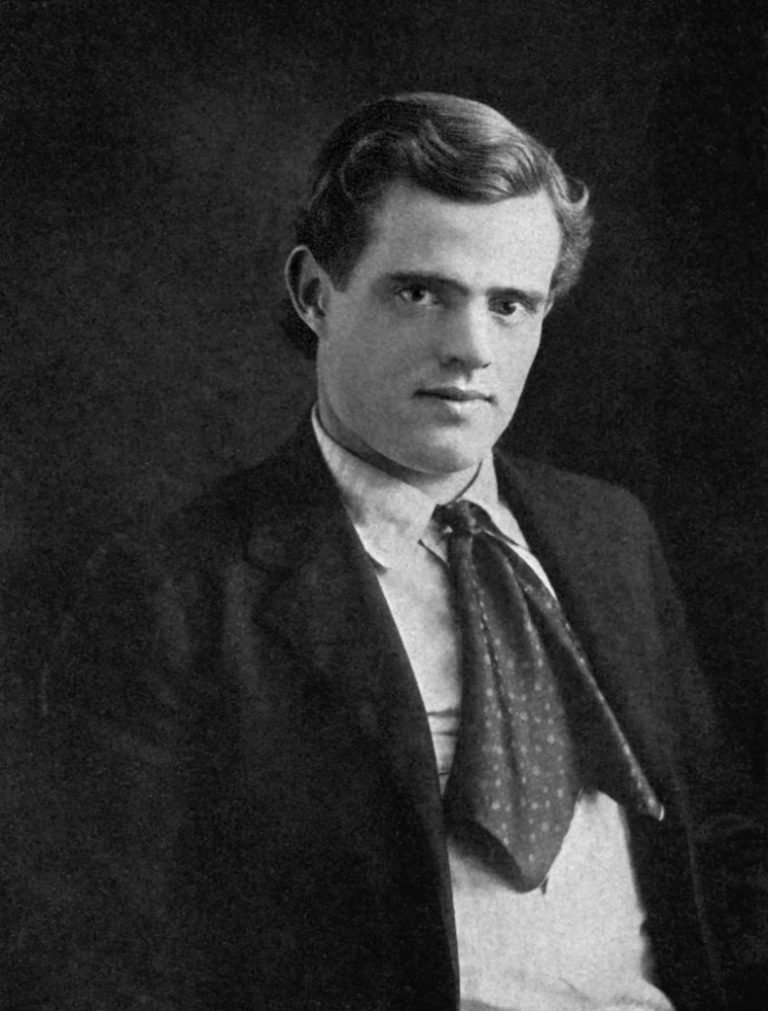

Jack London

Ninetta and Roscoe Eames, who had published London’s earlier writings in their journal The Overland Monthly, owned a small resort just off Warm Springs Road called Wake Robin Lodge. This is where he wrote his popular novel White Fang— and courted their niece Charmian Kittridge, who his biographer Russ Kingman called “Jack’s soul-mate, always at his side, and a perfect match.”

Over the next few years they purchased a series of seven neighboring farms they called the Beauty Ranch— known today as the Jack London State Historic Park.

Jack’s coterie of artists and writers increased with his fame over the years. Many came to Glen Ellen to visit and to stay, contributing to the bohemian alternative life style of the region that can be felt to this day.

Although entranced by the beauty of the Valley of the Moon, Jack London also recognized the ways in which previous farming methods had greatly damaged the environment. “I am rebuilding worn-out hillside lands that were worked out and destroyed by our wasteful pioneer farmers,” he once wrote to a friend.

Jack began building his dream house— the “Wolf House”— in 1911. “I am,” he wrote, “only just now beginning my first feeble attempts at building a house for myself. That is to say, I am chopping down some redwood trees and leaving them in the woods to season against such a time, two or three years hence, when they will be used in building the house.” And yet two years later, and just days before they were ready to move into their new home, a fire of unknown origin gutted the house in 1913, leaving only the rock walls and chimneys.

A visit to Jack London State Historic Park, at the end of London Ranch Road just a quarter mile north on Arnold Drive, is well worth an afternoon’s visit.

Hazen Cowan

Hazen Cowan (1890-1972) was raised on Sonoma Mountain, the oldest son of homesteaders James and Agnes Cowan. He and his brother were rough, tough rodeo riders, and as Jack London’s foreman he hauled rock from local quarries to help build the Wolf House.

Hazen often brought wild horses from Nevada and wild mustangs from Mexico that he’d either break and ride, or drive over Sonoma Mountain to the slaughterhouse in Petaluma. Jack London’s prize Shire stallion, Neuadd Hillside, arrived at the Ranch in 1913, the same hard year that his beloved Wolf House burned. Neuadd Hillside died just three years later, just months before Jack’s death. Charmian wrote this afterwards:

“I tell you, Mrs. London,” said Hazen Cowan, our cowboy, who had care of the stallion, “I hadn’t cried since the last time my mother spanked me, until Neuadd fell down. He wouldn’t lie down till he was dead, but stood there shaking all over.” Hazen pulled a freckled hand across his hazel, black-lashed eyes: “I’d really slept with him, lived with him, for months, you know.”

Hunter S. Thompson opened his story in Cavalier Magazine with this description of Cowan:

At a crossroads (here at Glen Ellen, Calif.), in the Valley of the Moon, in a weatherbeaten shack of a bar called the Rustic Inn, is a photograph taken in 1914 of a man named Hazen Cowan. It is a fuzzy, yellowed print, and kept under glass because the paper is getting brittle. It shows Cowan on horseback, wearing a white shirt buttoned at the collar and sporting a black head of hair. He is also wearing a slightly disbelieving expression that must have been common in those days when people looked into cameras. But the picture “came out,” as the saying goes, and you can tell by looking at it that in 1914 Hazen Cowan took no guff from anybody.

He still doesn’t, even though today he is an old and wizened man who gets around in a new Ford pickup instead of on horseback. His voice is still crisp with the ageless authority of an old soldier or a retired bandit, and in Glen Ellen he is a bit of a hero. He was a friend of Jack London’s: he worked for him and drank with him and he was the last man to see London alive. Around here that is quite a distinction…

Cowan is one of those men who likes to take his drink in the afternoon. On a slow day last summer he pushed in through the Rustic’s swinging doors and sat down at the bar in a stray beam of sunlight that poked through a dirty window on the street. The bartender, an earthy sort of country squire named Chester Womack, was holding forth with a guitar. “Hello, Hazen,” he yelled. “Say, the Missouri Kid was in here yesterday. Wanted to know if you were still fallen’ off horses like you used to.”

“That bum,” muttered Cowan. “He couldn’t ride in a wagon.”

Dr. Charles C. O’Donnell was a controversial figure, whose impact on Glen Ellen is felt to this day. He was born in Baltimore, Maryland in 1835, and came to San Francisco in 1854, where he established his medical practice by the early ’Sixties. Although he was charged with “conduct unbecoming an officer” in the National Guard and arrested for murder in what appears to have been failed abortions in the early ‘Seventies, he was acquitted of all these charges and went on to become a successful businessman.

O’Donnell helped organize the Workingmen Party, and served as a San Francisco delegate to the second California Constitutional Convention in 1878-79. There he argued vehemently against Charles Stuart, a delegate from Glen Ellen who strongly defended the Chinese.

In 1891 O’Donnell arrived in Glen Ellen to build a luxurious summer home called Cozy Castle, where he lived with his wife Emma and their son George, as well as in San Francisco where he continue to maintain his practice. He built an extensive mineral springs resort along Sonoma Creek in what became the O’Donnell Tract, which was described in detail in the 1898 atlas published by Reynolds & Proctor.

In 1903 coal and clay suitable for brick and pottery was discovered on his Glen Ellen property, and work began on constructing kilns in partnership with Joshua Chauvet, another early Glen Ellen entrepreneur. The California Brick and Pottery Company was organized in San Francisco with a capital of $40,000, under the operation of C. Hidaker and Joshua Chauvet’s son, Henry. The plant was capable of making 40,000 bricks per day at first, but by 1905 the kilns were firing 250,000 bricks.

Charles O’Donnell died May 1912 in San Francisco, at the age of 77.

Martin Eden

This illustration from a contemporary Whiskey ad is as close as we can get at this time to knowing what Martin Eden looked like. Jack London borrowed his name for one of his more famous novels. Several people remembered Eden in Bob Glotzbach’s book, Childhood Memories of Glen Ellen. Peggy Thompson remembered him “hauling hay and doing very heavy manual labor work. He had immigrated from Sweden and lived in a little one room cabin on Uncle George’s property. He’d walk up and do a day’s work and walk home.”

Anita Larkin said “Martin Eden was a frequent customer, and I remember once he came in, and i gave him change for a five dollar bill. He came back the following week and informed me that he had only given me a two dollar bill and returned three dollars; I remember that vividly.”

According to Glenn Purcell, “He lived right across the road and across the field on the Thompson property in a small cabin, probably eight by ten, pretty small. The shack’s still there; you can see it from the road, and it’s about ready to fall down. I always remember Martin as having a white beard and wearing black rubber boots. My father told me that Martin had been around for a long time and had showed him at one time how to pitchfork a steelhead. One night he went out with my father, carrying a lantern, and they went down to the creek in back of George Thompson’s house. Martin stood with the lantern in one hand and a pitchfork in the other, and he got two steelhead swimming in circles, smaller and smaller circles, until they got right under the lantern, and then down with the pitchfork. He got one of them. ‘There’s my dinner,’ he said to my father.”

“Hap” Arnold

A true pioneer, Arnold learned flight from the Wright Brothers, and became one of the first military pilots. He overcame a fear of flying due to his experiences with early flight, and rose to command the Army Air Forces immediately prior to U.S. entry into World War II, and directed its expansion into the largest and most powerful Air Force in the world.

Arnold’s most widely used nickname “Hap” was short for “Happy”, attributed variously to work associates when he was a stunt pilot, or to his wife, who began using the nickname in her correspondence following the death of Arnold’s mother in 1931.

During the war Alma Spreckels made her 2,100-acre ranch near Glen Ellen available to the troops at Hamilton Air Force Base. Arnold attended many high level military planning meetings in this peaceful setting throughout the war, and he deeply appreciated the serenity he found here. In 1943 he finally purchased his own ranch, “El Rancho Feliz” (the Happy Ranch) nearby on the flank of Sonoma Mountain, though it wasn’t until after the war was over that he could realize his life long dream to begin farming.

He became an enthusiastic host, as well. Over the next four years, until his death in 1950 at the age of 63, he and his wife entertained many guests such as Army general and Secretary of State George C. Marshall, Gen. James Doolittle, famed broadcaster Lowell Thomas, and California governor and Chief Justice of the United States Earl Warren.